Rising above a field in the scenic Illinois Valley, a billboard catches the eye. Its towering image shows a fair-haired boy, grinning for his kindergarten school picture. Beside the happy photo is a solemn plea:

“Every Overdose is Someone’s Child. Don’t Judge. Educate.”

Lori Brown authored that message after losing her son, Justin “Buddy” Pratt – the boy on the billboard who grew up, worked in a factory, loved to fish and explored the outdoors with his dog Meeko. Justin also secretly battled addiction and was found dead in his apartment after a heroin relapse at age 26.

“In my eyes, he didn’t reach out for help because he didn’t want to be categorized with a mental illness or substance abuse label,” Brown says. Her crusade to end the stigma of addiction and save others echoes a battle cry that’s growing stronger nationwide.

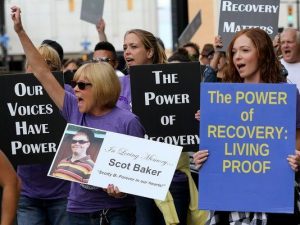

Bonded by the stunning loss from America’s addiction epidemic – drug overdoses continue to rise, killing a record 143 people each day – more voices are rallying for change.

They’re launching social media campaigns to confront misguided perceptions, and shedding anonymity as they share their own recovery stories on sites such as I Am Not Anonymous and Faces & Voices of Recovery. To shatter the stigma of addiction, parents are going public with their sorrow, stating drug overdose as the cause of death in a loved one’s obituary.

Nonprofits are popping up such as Brown’s organization, “Buddy’s Purpose,” which hosts recovery events and trains people in naloxone (Narcan), the lifesaving medication that can reverse an opioid overdose. Based on her conversations with families of opioid users, Brown estimates that 10 lives have been saved as a result of the training by Buddy’s Purpose. College campuses are also providing more formal support for students with substance use disorders; the number of collegiate recovery programs tripled between 2013 and 2015, according to the Association of Recovery in Higher Education (ARHE).

“I’m so glad that there seems to be a recovery movement happening. When we get to a point where people aren’t afraid to come out and talk about it, no matter what, that will be great,” says Crystal Oertle, a single mother in Ohio who is in recovery from prescription painkillers and heroin addiction. What has made a difference as much as the personal recovery stories, Oertle says, “is the mothers and other family members telling about daughters and sons who have paid the ultimate price from this disease, and overdosed.”

Like Cancer or Diabetes: A Disease, Not a Character Flaw

2016 was a watershed year for addiction awareness, led by grassroots advocacy and a series of “firsts:”

- The first time addiction became a central topic of a U.S. presidential campaign, with candidates sharing their personal family struggles related to drug problems and overdose

- The passage of the first and most comprehensive federal legislation to address addiction (the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016);

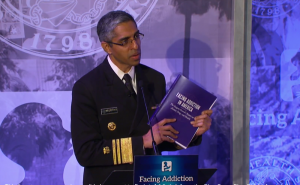

- The first-ever report on addiction issued by a U.S. surgeon general.

“For far too long, too many in our country have viewed addiction as a moral failing,” wrote Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, M.D., in his landmark report, released Nov. 17, 2016.

“This unfortunate stigma has created an added burden of shame that has made people with substance use disorders less likely to come forward and seek help . . . we must help everyone see that addiction is not a character flaw – it is a chronic illness that we must approach with the same skill and compassion with which we approach heart disease, diabetes, and cancer.”

Deadliest Year on Record, Again

More Americans are now dying from drug overdoses than from car accidents or gun homicides, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). And the toll is climbing.

In 2015, a total of 52,404 people died from drug overdose (143 per day) the deadliest year ever for the epidemic. The previous record was the year before, 2014, which had 47,055 overdose fatalities (129 per day). Most drug overdoses involve an opioid such as heroin, illicitly manufactured fentanyl or prescription narcotics, the CDC notes.

America’s struggle with painkiller addiction includes the high-profile death of music icon Prince, who overdosed on fentanyl in 2016. More powerful than heroin, fentanyl use has skyrocketed in the United States. Overdoses caused by synthetic opioids such as fentanyl rose 72.2 percent from 2014 to 2015, according to the most recent CDC data available.

A Cultural Shift?

Despite mounting death rates, only about 10 percent of people with a substance use disorder receive any type of specialty treatment, according to the Surgeon General and other sources. Fear of shame and discrimination is a key reason, along with the lack of screening for addiction and inability to access or afford care.

Oertle remembers the “No Junkies” sign on the pawn shop in her small Ohio town. “The other time I felt really stigmatized was at the hands of a doctor who was supposed to be helping me with my addiction,” she said. Oertle overheard the doctor treating another patient for opioid addiction and tell his nurse, “she would be better off overdosing under a bridge somewhere.” Oertle decided to seek help elsewhere.

One place that could be a turning point for recovery is the local police station. “Having law enforcement demand access to treatment is a game changer in the struggle to recognize addiction as a disease, not a crime,” says David Rosenbloom, Ph.D., an addiction expert and professor at Boston University School of Public Health.

“Thousands of individuals suffering from addiction are walking into police stations all over the country and getting immediate help into treatment and recovery because the cops won’t take “no” as an answer,” Rosenbloom says. “All too often, these same people have been turned away from emergency rooms and treatment programs that have stigmatized them as nuisances and ‘bad patients.’”

Changing the language of addiction to remove any implicit moral judgment is also gaining momentum, experts say. In late 2016, the White House Office of the National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) released guidelines that favor language consistent with current diagnostic practice. For example, the ONDCP recommends referring to a “person with a substance use disorder” instead of using the words “addict” or “substance abuser.” The latter are pejorative terms that have been shown in research studies to be viewed negatively by clinicians and more worthy of punishment instead of treatment.

More accurate portrayals of addiction in movies and television could also reduce stigma that hinders treatment, experts say.

Each year, the Entertainment Industries Council hosts the “PRISM Awards” honoring productions with realistic portrayals of substance use disorders and mental health concerns. Recent nominees include the film “Danny Collins,” which features Al Pacino as an aging rock star who struggles with drug and alcohol addiction, and the CBS show “Mom,” about a single mother (Anna Faris) who rebuilds her life in recovery (her mother, played by Allison Janney, is also in recovery).

“I have seen on-screen depictions of substance use disorders substantially increase over the past 20 years,” says Marie Gallo Dyak, President & CEO of the Entertainment Industries Council. “We have entire TV shows featuring addiction, treatment and recovery as major story lines for entire seasons.”

“This is very encouraging,” Dyak says, noting that “it’s the stories that reach families in their homes, with repetition that establishes an affinity to characters and their life situations, that have the potential to motivate the audience to seek help.”

“The distribution of health information is most effective when we have parallel movement among media and public policy,” Dyak says. “It is in the power of language and portrayals: what we hear, what we see.”

Lori Brown, who started “Buddy’s Purpose” in memory of her son, says we’ve made a “small dent” in changing the national conversation about addiction. Too many people still believe substance use disorders are the result of a character deficit or moral weakness, instead of a chronic but treatable illness, she says. “I think we have a long way to go to get to where we need to be.”

During her own family’s struggle, Brown says she felt isolation.“I don’t believe people shunned me. I believe people avoided me because they did not know how to deal with the delicate situation,” she says. “I think it (addiction) should be treated like any other disease. If your neighbor’s child has cancer, what are you going to say? ‘I’m going to prayfor you, if you need anything, I’m there.’” Brown says. “We need your support, your prayers, your acceptance.